Most of you are undoubtedly familiar with Intel and AMD, Qualcomm, Texas Instruments, and maybe even VIA, but there is one other chip maker you should be familiar with.

For the better part of a decade, Cyrix has brought the world of personal computing to millions of people in the form of cheap PCs, but the best product and the inability to control a popular game was followed by a bad merger with a more popular game. great. . Company.

The early 1990s were a strange time for the desktop computer industry.

Apple switched to IBM’s PowerPC architecture, while Motorola’s 68K chips lagged Commodore’s PC Amiga slowly on its grave. Arm was just a small flame founded by Apple and a few others, focusing almost entirely on developing processors for the infamous Newton.

This was around the same time that AMD released its processors from the negativity that was Intel’s inferiority. After cloning a few generations of Intel processors, AMD developed its own architecture, which was highly regarded for price and performance in the late 1990s.

This success can be attributed at least in part to Cyrix, a company that had the opportunity to conquer the home PC market and left Intel and AMD in the dust, but ultimately failed and quickly disappeared into the tech graveyard.

A humble start

Founded in 1988 by Jerry Rogers and Tom Brightman, Cyrix started out as a manufacturer of fast x87 math coprocessors for the 286 and 386 processors. These were some of the best guys to come out of Texas Instruments and they had big ambitions to beat Intel and beat them at their own game. .

Rogers began an aggressive search to find the best engineers in the United States and became the well-known leader of a team of 30 with an impossible task.

The company’s early math coprocessors performed about 50 percent faster than their Intel counterparts, but they were also cheaper. This made it possible to combine the AMD 386 CPU with the Cyrix FastMath coprocessor and achieve 486-like performance at a lower cost, which caught the attention of the industry and encouraged Rogers to take the next step and pursue the processor market.

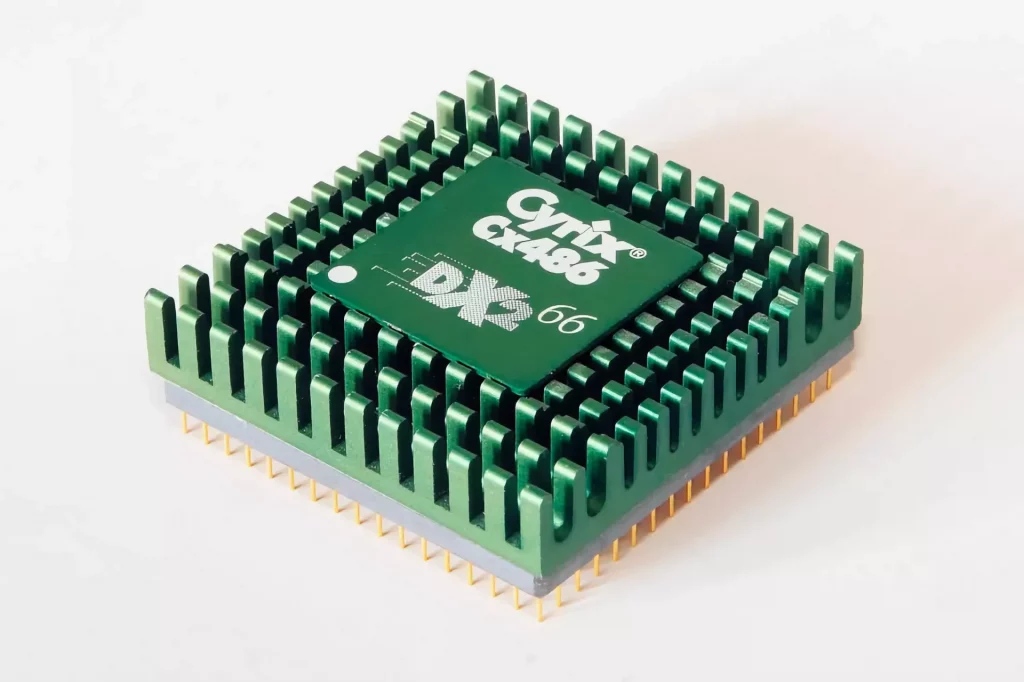

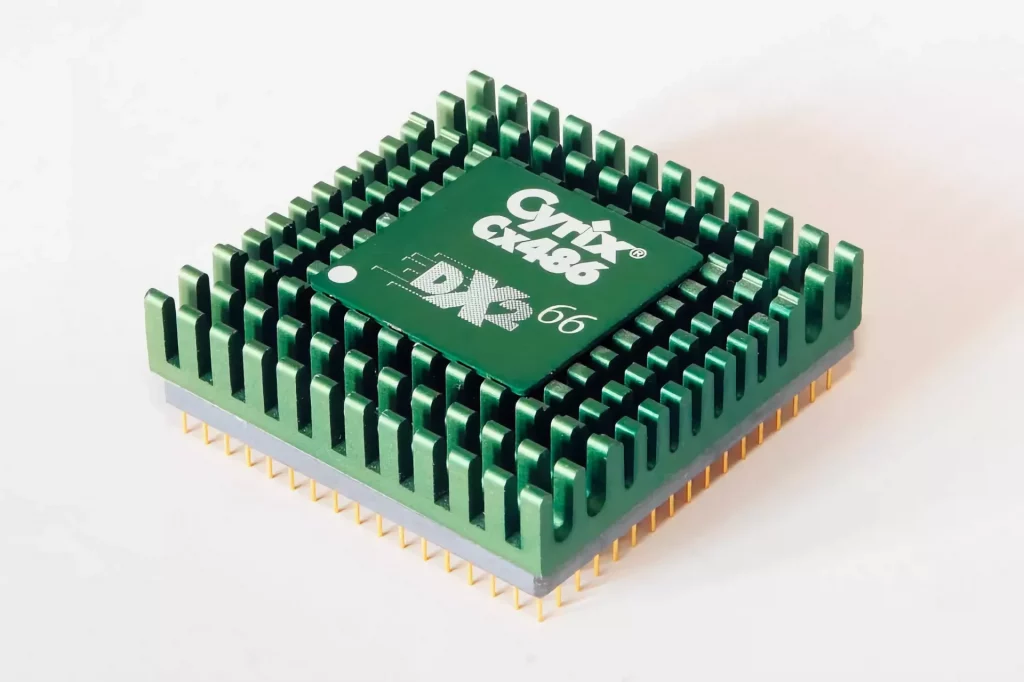

In 1992, Cyrix announced its first processors, the 486SLC and 486DLC, intended to compete with Intel’s 486SX and 486DX. They were also pin compatible with the 386SX and 386DX, meaning they could be used as incremental upgrades to outdated 386 motherboards, as well as used by manufacturers to sell affordable laptops.

Both versions offered slightly worse performance than the Intel 486 CPU, but significantly better performance than the 386 CPU. The Cyrix 486 DLC could not compete clock per clock with the Intel 486SX, but it was a full 32-bit chip and had 1 KB of L1 cache, but it cost a lot less.

The company’s early math coprocessors performed about 50 percent faster than their Intel counterparts, but they were also cheaper. This made it possible to combine the AMD 386 CPU with the Cyrix FastMath coprocessor and achieve 486-like performance at a lower cost, which caught the attention of the industry and encouraged Rogers to take the next step and pursue the processor market.

In 1992, Cyrix announced its first processors, the 486SLC and 486DLC, intended to compete with Intel’s 486SX and 486DX. They were also pin compatible with the 386SX and 386DX, meaning they could be used as incremental upgrades to outdated 386 motherboards, as well as used by manufacturers to sell affordable laptops.

Both versions offered slightly worse performance than the Intel 486 CPU, but significantly better performance than the 386 CPU. The Cyrix 486 DLC could not compete clock per clock with the Intel 486SX, but it was a full 32-bit chip and had 1 KB of L1 cache, but it cost a lot less.

At the time, enthusiasts loved that they could use the 33MHz 486DLC to achieve similar performance to the 25MHz Intel 486SX. However, it was not without its issues, as it could cause stability issues on some older motherboards that they had no additional cache control lines or CPU register control to enable or disable internal cache.

Cyrix also developed a “direct replacement” variant called Cx486DRu2, and later in 1994 released a “clock doubled” version called Cx486DRx2 with the cache coherence circuit built into the CPU itself.

By that time, however, Intel had released its first Pentium CPU, which lowered the prices of the 486DX2 to the point that the Cyrix option had lost its appeal, as it was cheaper to upgrade to a 486 motherboard than to buy a Cyrix. . . old 386 motherboard. When the “triple clock” 486DX4 arrived in 1995, it was too little, too late.

Major PC makers like Acer and Compaq were not convinced by Cyrix’s 486 processors and opted for AMD’s 486 processors instead. However, that didn’t stop Intel from taking years to court and claiming the Cx486 infringed its patents and never won the case.

Cyrix and Intel eventually settled out of court, with the latter agreeing that Cyrix had the right to produce their x86 projects at foundries that were cross-licensed from Intel, such as Texas Instruments, IBM, and SGS Thomson (hereinafter STMicroelectronics).

Never repeat the same trick twice … unless you’re Cyrix

Intel released the Pentium processor in 1993, based on the new P5 microarchitecture, eventually getting a name that fits the market. Above all, it raised the bar for performance and ushered in a new era of the personal computer. A new superscalar architecture made it possible to execute two instructions per clock, an external 64-bit data bus made it possible to read and write more data with each memory access, a faster floating point read unit that provided performance up to 15 times higher than those of the 486 FPU and many other subtleties.

Cyrix took on the challenge of recreating a middle ground for Socket 3 motherboards that couldn’t handle the new Pentium CPU before that model was even ready to ship. That middle ground was the Cyrix 5×86, which at 75 MHz offered many of the features of fifth-generation processors like AMD’s Pentium and K5.

The company also made 100 MHz and 133 MHz versions, but did not have all the advertised performance enhancement features, as they would cause instability if used and the overclocking potential was limited. These were all short lived and after six months Cyrix decided to stop selling them and switch to another processor.

Through the lens of Peak Cyrix Quake

In 1996, Cyrix introduced the 6×86 (M1) processor, which was supposed to be yet another replacement for the older Intel processors in the Socket 5 and Socket 7 motherboards with reasonable performance. But this wasn’t just an upgrade path for cheap systems, it was actually a small miracle in processor design that was deemed impossible: it combined a RISC core with many CISC core designs. At the same time, it continued to use native x86 execution and standard microcode, while Intel’s Pentium Pro and AMD K5 relied on dynamic microfunction translation.

The Cyrix 6×86 was pin compatible with the Intel P54C and had six versions with a confusing naming scheme that should have indicated the expected performance level, but was not a true indicator of clock speed.

For example, the 6×86 PR166 + only ran at 133 MHz and was marketed as being equal to or better than the 166 MHz Pentium, a strategy that AMD then repeated.